“IT WAS AN AGE of art, it was an age of excess,” said F. Scott Fitzgerald of the flapper era. The word “flapper” had been around for a while by 1920, the year he published This Side of Paradise, the post-World War I novel that would define a generation. It meant variously a young woman about to leave the nest (and thus flapping her wings); any giddy, impetuous young woman; and finally, the drinking, smoking, cursing, jazz-loving, short-skirt-wearing bad girl of the 1920s.

“IT WAS AN AGE of art, it was an age of excess,” said F. Scott Fitzgerald of the flapper era. The word “flapper” had been around for a while by 1920, the year he published This Side of Paradise, the post-World War I novel that would define a generation. It meant variously a young woman about to leave the nest (and thus flapping her wings); any giddy, impetuous young woman; and finally, the drinking, smoking, cursing, jazz-loving, short-skirt-wearing bad girl of the 1920s.

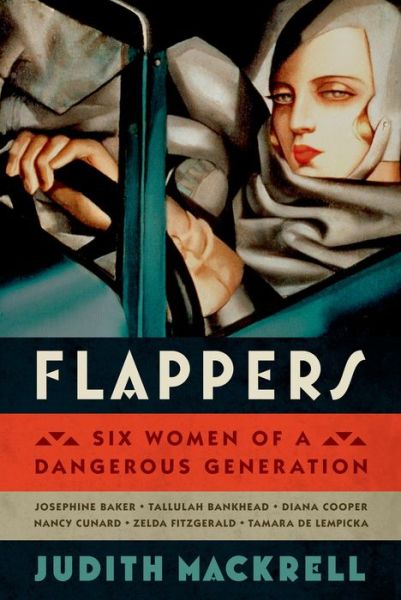

In Flappers: Six Women of a Dangerous Generation, Judith Mackrell’s bold, bawdy, and somewhat maddening collection of mini-biographies of six infamous women who more or less met that description, the term is loosely applied. In the same way that “hippie chick” has come to mean anyone who’s ever worn a flower skirt while parting her hair in the middle, flapper appears to be a catchall term for young women of a certain era who acted out, flaunted traditional expectations, drove their parents up the wall, and inspired hand-wringing op-ed pieces in the respected newspapers of the day.

Mackrell, a respected British dance critic and author of an acclaimed biography of Russian ballerina Lydia Lopokova, has selected her flappers with an eye toward diversity. Lady Diana Cooper, the youngest daughter of the eighth Duke of Rutland and the artistically inclined Violet Lindsay, was famous for carousing with a group of raucous intellectuals, the Corrupt Coterie —“Our pride was to be unafraid of words, unshocked by drink and unashamed of ‘decadence’ and gambling,” she said — most of whom died during World War I; she later married scandalously beneath her station. Nancy Cunard, daughter of an English baronet and an American heiress (cue Downton Abbey theme music) and scion of the Cunard shipping line, married disastrously, moved to Paris, wrote poetry, and served as a muse to various celebrated men, including Aldous Huxley. Tamara de Lempicka, a tempestuous and glamorous Polish-born refugee from Imperial Russia, was too disciplined, industrious, and ambitious to be considered a true flapper, but nevertheless made a fortune depicting them in her wildly popular Art Deco paintings. Tallulah Bankhead, born into a powerful Alabama political family, left home for New York to become an actress at 15 and became infamous for her cartwheels, performed without underpants, and her shocking remarks. (“My father warned me about men and booze, but he never mentioned a word about women and cocaine.”) Pampered Zelda Fitzgerald, also born into a socially prominent Alabama family, came to symbolize the jazz age, United States division, by virtue of being christened “the first American flapper” by her famous novelist husband. And Josephine Baker, illegitimate child of unknown paternity, raised in a St. Louis ghetto, eventually became the toast of Paris and the first African-American woman to star in a major motion picture (Zouzou in 1934).

Mackrell’s prose is nimble and authoritative, and she succeeds in conveying the degree to which a lot of flapper behavior was shocking, not just in the context of the times, but even now, in our relatively conservative post–sex, drugs, and rock era. There is, in this book, no shortage of booze, drugs, threesomes, STDs, and unsavory acts of exploitation. Likewise, she doesn’t flinch in the face of grubby reality in an otherwise highly romanticized era. Her explication de birth control circa 1918 — “the only ways to avoid getting pregnant were using vinegary-smelling douches or the thick Trojan condoms their lovers might have picked up from a barber’s” — is in equal measures icky and sobering, and she confirms what pretty much every mother whose daughter wanted to be an actress in the early 20th century suspected: putting out, early and often, was part of the game.

Determined not to play favorites, Mackrell takes great pains to portray each of her subjects (all of whom she calls by their first names) with the same degree of empathy and respect, and she wades purposefully into their childhoods and young adult misery. Cunard was raised by a tyrannical governess (cold baths, unsweetened porridge, and enforced French verb memorization). Cooper nearly gave her mother a stroke by volunteering as a nurse at one of London’s “squalid” public hospitals during the War. With the exception of Bankhead, whose mother died of peritonitis three weeks after she was born, every story seems to feature a mother against whom the daughter must rebel. Plus ça change.

Admirably and wisely, Mackrell resists the urge to cast her flappers as “nice,” then as now a hallowed female imperative. Most of them were titans of self-absorption verging on narcissism; trying to play up any traditional feminine “angel in the house” business would have been a mistake. As she writes of fiercely ambitious opportunist de Lempicka, “she had so little talent for empathy.” She reminds us often that Fitzgerald routinely seduced men beneath her husband’s nose, usually out of boredom. Gatsby’s idiotic and careless Daisy Buchanan was modeled on her.

But perhaps Mackrell is almost too scrupulous in her effort to be objective. It’s unclear whether she’s simply committed to democracy of interpretation, or unmoved by the horrors of racism in America, but even Josephine Baker — who was farmed out as a scullery maid at age seven, and whose Christmas when she was nine included being beaten until she was covered in welts while being told by her mother that she hated her — is taken to task for her penchant for self-dramatization. “Josephine was no less of a myth maker than Tamara,” Mackrell writes, “and couldn’t resist exaggerating and editing her life into a more dramatic shape.”

Each mini-bio captivates, but the curious structure — the stories are divided in half and braided together — creates juxtapositions that sometimes strike the wrong note. After reading of Baker’s harrowing early years, which make the life of a Dickens orphan look like something out of Gossip Girl, Mackrell deposits us back in the life of Lady Diana, where we learn she is afraid to tell her mother that she is going to marry the unsuitable, insufficiently well-bred Duff Cooper. Are we really to equate Diana’s discomfort at thwarting her mother’s expectations that she marry well with Josephine Baker’s unfathomably wretched childhood in the ghetto of St. Louis?

Not surprisingly, Mackrell possesses more natural affinity with Cooper and Cunard, her fellow Brits, and de Lempicka, all of whom suffered deeply from the trauma of the Great War and whose devotion to pleasure and living in the moment take on a profound and existential cast in the face of a war that decimated an entire generation of men. Of Cooper she writes, “She knew her behaviour was risky, but she found it addictive: the exhilaration of being ‘dangerous, dissipated, desperate’ kept the nightmares of war at bay.” Mackrell notes, and rightly so, that none of her American subjects even knew the world was at war when their own country entered it in 1917, our obliviousness to what’s going on elsewhere being one of our most shameful and enduring national characteristics.

Maybe this is why the sections on Bankhead and Fitzgerald seem a bit superficial. All of the women were concerned with their own happiness above all, but those who were the victims of the times, of war or poverty and racism, are operating out of a more complex human experience than these two women, who were, let’s face it, simply spoiled. Indeed, the Fitzgerald section is as much about her husband as it is about Zelda, who, despite her role as flapper/muse, was not a lot different than most women of her time and class.

But this is a quibble. Mackrell has assembled a cast of astounding women who were not afraid to embrace life and follow their passions, come what may. Their refusal to go along with what was expected of them at the end of the Edwardian era nudged along the cause of female emancipation, showing the world that just like men — for better or for worse — women could make of their lives what they willed.

The Los Angeles Review of Books is a nonprofit literary and cultural arts organization that combines the great tradition of the book review with the evolving technologies of the web. We are a community of writers, critics, journalists, artists, filmmakers, and scholars dedicated to promoting and disseminating the best that is thought and written, with an enduring commitment to the intellectual rigor, the incisiveness, and the power of the written word.