The other day my phone died. The Man of the House took it to Sprint to see what was the what, and I was left phoneless. I put on my watch, which I haven’t worn since I started using my phone to check the time (maybe 2008) and marveled at the elegance of the invention. You want to know the time? No digging in your bag, no madly pressing tiny buttons or furiously tapping at a blank screen — BAM, there it is, right on your wrist.

I needed to let off some steam, so I went for a run in my neighborhood. In kindergarten I was diagnosed with what was at the time called “hyperactivity,” now known as ADHD, and my mother’s home grown solution was to send me on a run around the block. Whenever I need to regroup I still “run around the block.”

Usually I take my phone, but my phone was dead. I briefly considered skipping it, because how could I possibly venture out for forty-five minutes without my phone? What if an interesting email arrived? What if something got retweeted or someone wanted to add me on Goodreads or LinkedIn, the password to which I’ve long forgotten, has sent me an update?

But I pushed myself out the door, and three blocks later I was filled with the same euphoria I’d felt decades ago, standing in the dawn mist on the deck of the U.S.S. Universe Campus, the ship then employed by the college aboard program, Semester-at-Sea, as we pushed out from Port Everglades, Florida, headed across the Atlantic to Morocco.

I felt free and wild! I was living with abandon!

This is what it’s come to: a short trot around my nice Portland neighborhood in broad daylight without my digital tether felt like the height of adventure.

The Merriam-Webster defines “abandon” rather inelegantly as “to give oneself over unrestrainedly.” But most of us are nothing if not restrained these days. Restrained, constrained, every other strained you can think of. If you’re in doubt, consider: never in the history of our nation have women spent more time fretting over the state of their pubic hair.

To live with abandon means, on the face of it, to cut loose, to see what happens next, to refuse to plan. There’s one of those big idea-in-a-small-format book called Improv Wisdom: Don’t Prepare, Just Show Up by Patricia Ryan Madison that captures the spirit of living with abandon. She preaches getting up in the morning, brushing your teeth, making your bed and seeing what happens.

Living with abandon isn’t exactly a synonym for spontaneity, however. It’s also about being all in. My friend and co-author Gabby Reece is married to big wave surfer Laird Hamilton; no one has a better sense of what it means to be all in than he does. When he decides to launch himself down a wave as tall as a three story building, being all in, committing 100% to the experience, is a life and death issue.

For a lot of us, it seems as if the only time we give ourselves over wholeheartedly is at karaoke night, after a tankard of mojitos.

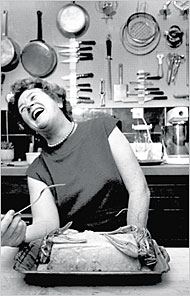

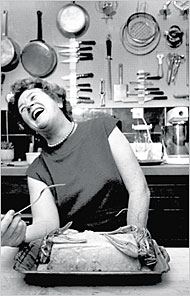

Julia Child didn’t discover her passion for cooking until she was staring down the barrel of forty, but then she was all in. She spent every waking hour devoted to food and cooking. She was fortunate in that she had a trust fund from her mother, most of which wound up in the register at E. Dehillerin, arguably the world’s best kitchen supply store.

Sometimes she bought so much stuff she needed to make two trips in the big Buick she and Paul had shipped from the states. She overspent, over-ate, and over-committed. She got involved with two difficult French women who had a hare-brained idea about writing a French cookbook for American cooks and her world was never the same. Notice please: Julia fell in love with an exacting cuisine that required discipline, rigor and yes, restraint. But she approached it with abandon.

Living with abandon, according to Julia, meant being fearless, making mistakes, and accepting that the fear and the mistakes were part of the fun. She really didn’t care too much if she messed up. Her default setting was not to stand back and ponder, but plunge ahead and fix it as you go along. Or, do it again. There are many Julia stories about how many times she was willing to retest a recipe to get it right. It was all boots on the ground with her, she was all in all the time.

I’ve heard tell that on Thanksgiving Julia’s phone would ring all day long, with people wanted to know how to make a stuffing that wasn’t soggy, or what to do with a runny gravy. Long after she was rich and celebrated, she would always answer that phone. Because who knew who might be on the other end? Who knew who she might meet or help?

Julia’s phone hung on her kitchen wall, of course. She had no choice about whether to take it with her or leave it at home, and she didn’t have to wait for it to break to live, even for a moment, with a feeling of abandon.

sources: Laird Hamilton, swellseekers.ie, photo Benjamin Thouard; “Josh and I,” vibrantsignificance.wordpress.com; Julia Child, New York Times, Marc Riboud/Magnum

Join the discussion One Comment